Fieldwork and Research trip | North Coast & South Sinai, Egypt

TRIP INTRODUCTION:

This trip was the first of our field work and studies in Egypt within ACTIVATE’s larger and ongoing regional EM/MENA Project, which addresses issues surrounding the growing water and food crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and North Africa. The results of the first stage of this collaborative project were presented at the “2017 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism”, within both its sections, the Cities and Thematic Exhibitions.

Initiated through the generous invitation from the Center for Sustainable Development Studies (CSDS) of the historic Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the purpose of this trip was to collect preliminary information and data regarding some of the ongoing environmental challenges that have led to critical issues such as water stress and food insecurity in disparate areas such as the delta and arid regions of the country. These problems are worsening due to the increasing impacts of climate change, and are affecting both the land and the livelihoods of people.

An intensive program of site visits and field work began in the urban location of Alexandria and the areas surrounding the city in the Nile Delta (Kafr El-Sheik) that have been affected by sea level rise and salt water intrusion, in order to partially evaluate the current conditions. This was followed by a visit to an area representative of Egypt’s dry regions, the Egyptian Western Desert (Marsa Matrouh), and then by plane to the southern half of the Sinai Peninsula, the least populated governorate of Egypt, to visit farms along the Red Sea (Nuweiba).

The objective of this trip was to meet with representatives from various environmental agencies, but moreover, to visit with people working ‘on the ground’ in all of these areas who in many cases live under harsh changing climate conditions, to obtain preliminary on-site knowledge about the way they are constantly adapting to the environmental and socio-economic changes. Moreover, to evaluate and discover how people are building resilience measures in these different regions, and listen to the new ideas and solutions being used to be more resilient to the impacts of climate change. Our hope is to begin to help to transfer this practical knowledge and incorporate these responses — bottom up — with suggestions to local representatives and policy makers for better sustainable development in each region.

Flag at the Salahuddin Citadel, Taba, S. Sinai

The team in Egypt, to which we are most grateful, was led by Dr. Salah A. Soliman, Director of the CSDS of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, who has also been Professor of Pesticide Chemistry & Toxicology at the University of Alexandria since 1985. Dr. Soliman is the founder of many activities in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina including international conferences and meetings focusing on environmental affairs, science and technology, in addition to many activities to build capacities of students. Our collaboration had its roots in a first meeting at a 2016 CyI Conference on WEF Nexus applications in the MENA area, with the intention to begin preparing for a long term interdisciplinary collaboration that would address issues surrounding the global water and food crisis in the region.

From the CDSD was also scientist Dr. Riham Abd El Hamid, project manager and responsible for Center’s activities and programs, who was also in charge of the logistical organization of the trip.

Also joining the team was colleague Dr. Ahmed Imam (PhD, Entomology) associate professor and head of the Bio-Control Unit of the ‘Sustainable Development Center for Matrouh Resources’, a regional station of the Desert Research Center. (The DRC is one of the oldest scientific research centers in Egypt and now part of the Ministry of Agriculture & Land Reclamation, whose overall objective is to conduct research on the natural resources in the Egyptian deserts). In Marsa Matrouh the SDCMR addresses sustainable agriculture development under the rain-fed conditions of the Egyptian Northwestern Coast. With his expertise in Biological control, Imam and the technical staff of Bio-Agri mission includes: the application of environmental management practices for domestic desert cultivations of the indigenous Bedouin local communities; the biological control of insect pests under desert conditions; and the study of insect biodiversity and desertification and land degradation mitigation.

Also, Dr. Yousria Hamed, Egypt’s first female Park Ranger, and specialized in Community Sustainable Development, Protected Area Management and Communication, Education and Public Awareness. Among her areas of expertise is the role of traditional knowledge as an important part of sustainable development, and its value in contemporary education. Her work includes conservation, upgrading farming practices, and recording traditional techniques from Bedouin traditional knowledge in the Protected Areas of Egypt. Currently she is UNDP Project Manager of Support to the Protected Areas of Egypt Project.

Joining us for the northern leg of this trip was long-time ACTIVATE partner, curator Prof. Hyewon Lee from South Korea; and from Alexandria, photographer Mohamed El Baroudy.

Below is some compiled research information, and images from the trip.

Egypt is a Mediterranean country and the most populous nation in North Africa and the Middle East with a total land area of 995,450 km2. It has a dry and arid climate, and roughly 96% of its total territory has a desert landscape, an area which is sparsely inhabited. This climate is categorized as arid in the north (Alexandria) to extremely arid in the south (Aswan). The entire Nile Basin covers 3,250,000 km2 and its delta forms at the mouth of the Nile, the world’s longest river (~6700 km). Egypt’s water is derived from its two north-flowing branches, the Blue and White Niles, that merge as the Main Nile in the northern Sudan.

Egypt’s population will surpass 99 million in 2018. These inhabitants reside mainly in the 3% of its territory that has arable land, most of which located in the Nile River flood plains and Delta area, plus a few other green small zones found at oases and on the northwestern coast.

In other words, 98% of Egyptians live on about 3% of the nation’s territory and of these, roughly half of the country’s residents live in urban centers (38.7 % of the population is urban, in 1955 the amount was 8.5 million, today it is 38.5 million) – in Egypt’s capital Cairo, in coastal city of Alexandria, and other cities located in the Nile Delta area.

With a rapidly increasing population, Egypt has seen a marked by a rural-urban migration flow which has resulted in a tremendous growth of the main cities. The expectation indicates that the size of Egyptian population to grow to 128 million by 2030, and 153 million in 2050 if fertility and growth rates remain the same of above 2.0%/yr. Urbanisation goes hand in hand with challenges like climate change, land degradation, food security, water scarcity and many others. By 2050, more than 60% of the world population is estimated to live in cities.

ALEXANDRIA and the NILE DELTA, North Coast

Map of North Coast, indicating the locations of Marsa Matrouh to the West, the coastal city of Alexandria, and the governorate and city of Kafr El Sheikh in the Nile Delta | Click to enlarge.

Dusk in the city of Alexandria

Alexandria

About 10 million people inhabit the northern delta’s coastal region. This number includes the 5 million people living in Alexandria, Egypt’s second largest city and its major port and industrial center. Population densities are extremely high (up to 1000 or more/ km2) in much of the Nile delta and valley.

The entire coastal zone of Egypt is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, not only because of the impact of sea-level rise, but also because of the impacts of water shortage, agricultural practices, and increased human activity in urban zones.

Climate change has also affected the urban life of Alexandria. The city’s population continues to grow due to hundreds of thousands of forced migrations each year from nearby villages affected by sea level rise (SLR), and other adverse effects of changing climate trends. These changing realities in the socio-economic identity of their residents of Alexandria have brought alterations to the city; unguided urban planning has resulted in the construction of thousands of illegal and unsafe high-rise buildings within its narrow streets, and along its seafront road. Many new slums have appeared, dispersed through the city center and in peripheral neighborhoods.

Egypt is considered one of the top five countries expected to be mostly impacted with about 1.0 m SLR in the world as a result of global warming. The UN-Habitat Program foresees that a sea level rise of just 50cm in the Mediterranean will lead to major coastal erosion and flooding, that could eventually force 1.5 million people in Alexandria to abandon their homes. This would also wipe out 214,000 jobs, cost $35 Billion in lost property and tourism income, and cause further destruction to the city’s historic sites. Such predictions do not even take into account the human and environmental repercussions of extreme events, such as tsunamis and earthquakes, to which Alexandria is increasingly exposed.

READ MORE about urban environmental challenges in our ALEXANDRIA Project at the Seoul Biennale 'Cities Exhibition' →

Nile Delta

The Nile Delta is the fertile coastal zone along the Mediterranean Sea that has been the farmland breadbasket of the country throughout its history. As a low-lying zone however, it is now a vulnerable area due to sea level rise and local land subsistence. In ancient times, through agricultural production and irrigation methods using the water from the Nile’s annual floods, Egypt was able to create enormous wealth; today too, agriculture is an important sector in the Egyptian economy. The rapid growth in Egypt’s population over the past decades brought about an intensification of cultivation almost without parallel elsewhere.

However, with climate change causing the Mediterranean Sea’s waters to rise (SLR), both vegetation and farming along the northern coast of Egypt have been greatly affected. Today growing environmental impacts are threatening water resources, agricultural activity and the livelihood of the coastal population. Experts project that by the end of this century, SLR could create millions of climate refugees, and have an enormous impact on the Egypt’s agriculture and economy (the agricultural sector provides work for approximately 35% of Egyptians and produces 14.8% of Egyptian gross domestic product ), as any harm to the agricultural sector from SLR will translate into a lower Egyptian GDP.

The agricultural practices of local farmers in the Delta agricultural lands have in fact been changing since the since the early 20th Century as a way to adapt to increasingly difficult conditions: water scarcity, saltwater intrusion into the Delta that has resulted in salinated soil, and the overuse of sand from the coastal dunes whose purpose is to serve as a protective belt, formed by sediment discharge from the Nile. The constantly expanding human activity over the last few decades is exacerbating all of these issues.

SOIL: Today, increasing salinity in the delta plain - which lies only 1 meter above sea level - has rendered the basin’s soils less capable of producing food and fresh water. In this once nutrient-rich area that generated 60% of the country’s food production and for decades alone provided Egypt’s both food and water, today this Delta region is facing a continued reduction in useable land and fresh water supply needed for agricultural production. The soil of this degrading farmland from growing salinity may ultimately render the delta’s soil incapable of agricultural cultivation and effectively cut off the area’s fresh water supply. Soil salinity is exacerbated by irrigation with low quality (saline) water, and sea-level rise continuing to contributes to saline water intrusion into the delta’s aquifer. Egypt currently suffers from soil salinization in ca. 35% of its soils, mostly located along the northern strip of the Nile Delta, which has become a grave threat to the future food security of all of the country; Egypt must import much of its food to feed its growing population concentrated in the Nile delta and its valley.

WATER: A fresh water crisis now looms entire region of the Middle East and North Africa. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that the region will see more than a 50% drop in accessible fresh water by 2050, and such a scenario could ultimately make the entire region of uninhabitable by the end of this century. In Egypt, this crisis already threatens nearly 100 million people. In the Delta area, since the 1990s, water has increasingly been diverted to the growing city of Alexandria. Coupled with the environmental issues and the expansion of rice production, farmers along the Nile water canals are dealing with a significant decrease in water availability and are barely able to meet their irrigation needs during the summer months. Moreover, excessive rates of groundwater withdrawal has resulted in a large drop in the water table and, as a consequence, seawater continues to intrude into the aquifers. As Egypt has one of the world’s lowest per capita water shares, and with its population expected to double in the next 50 years, Egypt is projected to reach a state of serious country-wide fresh water shortage by 2025.

SAND DUNES: Another coastal challenge is the overuse and loss of sand from the coastal dunes. In the past, most of the 50 km wide land strip along the coast was protected from flooding by this coastal sand belt formed by the sediment discharge of the Rosetta and Damietta branches of the Nile. Currently, there is an urgent need for the preservation the remaining dunes, this protective sand belt, which have been facing erosion since the construction of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s; prior to the Dam, the Nile flooded annually, depositing both sediment in the Delta and replenishing Egypt’s soil. Ongoing quarrying of sand dunes along the delta coast for mineral mining and agricultural applications continues to remove this natural protective barrier that backs the low-lying shoreline, and there is little sediment available for coastal replenishment. Moreover, researchers say that the northern third of the Nile Delta is the submerging at about 1 cm of terrain per year; it is projected that between 12 and 24 miles of presently dry delta surface will be under water by the year 2100.

Overall, the need for coastal adaptation to sea level rise along the Nile Delta is urgent; this area can remain safe from projected flooding during the current century only with effective integrated coastal-zone management, in order to avoid the possible displacement of over two million people. In the past thirty years, the Government of Egypt has addressed these issues by implementing sea erosion reduction and shore protection measures. In areas of high-risk vulnerability in Alexandria and the Delta area, some adaptive actions have also been taken in cooperation with local communities to reduce effects of climate change, and to safeguard livelihoods in environmentally-affected areas. At present, the targets that have been set for 2030 will address impacts of SLR on the water resources of Egypt, and all the other projected environmental issues and challenges of the future.

Kafr El-Sheikh

The first leg of our trip was to the governorate of Kafr El-Sheikh, to visit the sites affected by climate change and sea level rise, and see the issues most affecting the land and its people.

Images from around the area

Kafr El-Sheikh is one of the 27 governorates of Egypt and is located in the northern part of the country along the western branch of the Nile, in the Nile Delta. Its capital is the city of Kafr El-Sheikh (see map above).

Agricultural practices in this area have been shifting since the early part the 1900. Since then, farmers have been adding topsoil (from the sand dunes along the coast) to the land in order to restore its fertility and be able to grow crops, which became progressively more difficult due to the increasing salinity of the soil from the intrusion of seawater into the region’s groundwater. The removal of the sand dune topsoil, however, increases the levels of water intrusion. As groundwater in the aquifers is salinated, farming requires more water from irrigation. Another challenge to the local farmers are the many invasive species, that destroy everything from tomatoes to palm trees.

Today, Egypt is losing its fertile lands and people in areas with higher population are being displaced.In the past, farmers were adding 1m of topsoil about every 25 years; today, it is needed every 5 years. As topsoil is costly, farmers have abandoned cash produce such as fruits and have been shifting towards growing rice and also to fishing. Likewise, if farmers cannot afford topsoil, they must leave and abandon their villages.

Coastal Sand Dunes

Dr. Soliman explains:

“The density of sand is 2tons/cubic meter. Along the coast in the past, this sand caused pressure on the soil of the ground of the shoreline beneath it, compacting the silt and naturally slowing the intrusion of saltwater into the land —

When the dunes began to be removed, the pressure was also removed, causing the silt below to expand and become more porous to saltwater —

The ground for even kms from the shoreline have become salinated, as has the soil that is used as farmland, and the water within it.”

MARSA MATROUH, Northwestern Mediterranean Coastal Region

Reversing the Cycle of Desertification

Marsa Matrouh, on the northernwestern coastal zone of Egypt (NWCZ) is located in the western desert of Egypt. This area stretches along the Mediterranean, about 360 km west of Alexandria and the Nile Valley; the Libyan border is westward. The area extends for roughly 400 km, and inland for roughly 50 km; to the south of this area is the northeastern Sahara. The region has a desert climate of about 100–200 mm of rain a year, which follows the Mediterranean pattern of falling during the winter months between November and March; precipitation is usually low and erratic. This arid region suffers both water scarcity and food insecurity, and is settled by Mediterranean Bedouin tribes, an agricultural community of 40,000 people. Although it covers over 16% of the nation’s geographic area, it is disadvantaged governorates, being one of the poorest in Egypt.

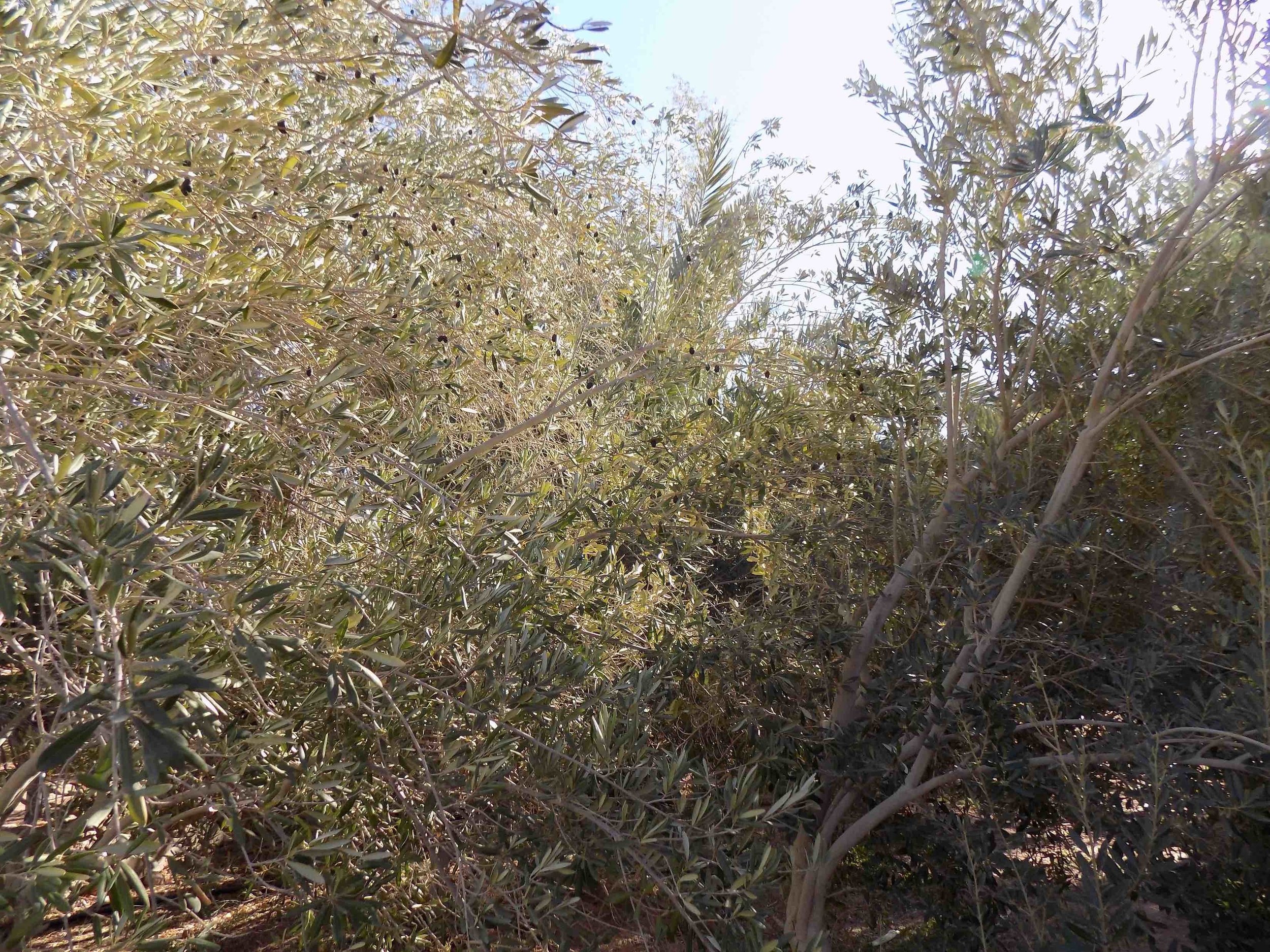

Historically, the land was pastoral desert rangelands, grazed by nomadic Bedouins moving their animals continuously across the expanse of the area. However, following WWII, this Bedouin population became settled and reside in permanent homes. Their animals now graze in the same general areas around the settlements year round, which has contributed to the dryness of the land due to overgrazing. Today, agriculture is the main source of livelihood for 70% of the population, who raise sheep and goats and cultivate mainly figs and olives.

The area along the coast is made up of over 218 valleys (wadis) that stretch down towards the Mediterranean coast. Over the past years, these farmers in the area have begun a shift to sustainable dry-land agricultural practices and implementing multiple water catchment techniques—such as the construction different types of dykes or checkdams along these valleys— as catchment areas for the winter rainfall which often come as flash floods, the sole source of water for irrigating these trees.

Purpose of our visit to Matrouh Governorate was to see the adaptation and resilience in pastoral management of the Bedouin social-ecological system in the NWCZ, and to see their natural water management strategies and water harvesting capabilities. Moreover, to see how some government programs which have been implemented have facilitated a shift to sustainable dry-land agricultural practices.

We were kindly hosted at the ‘Sustainable Development Center for Matrouh Resources’ of the Desert Research Center.

As a result of the growing rural-urban migration flow throughout Egypt and swelling of population in its main urban centers, the Egyptian government has implemented several development programs, one of which is in the coastal zone of the western desert. This was begun in the NWCZ through a series of needs assessment meetings organized by the Desert Research Center with the Wadi local community, to get their feedback before proceeding with the project.

The ongoing mission of the DRC is to help conserve the natural resource base (water, land and vegetation) and to implement programs to alleviate poverty and improve the livelihoods of the rural Bedouin population by providing support to improve sustainable resource management practices, and for agricultural production improvement and socio-economic development, including training programs, income generating activities, and enhancing the role of women.

Other objectives are to protect and enhance water resources by increasing the role of supplemental irrigation to conserve rainwater for crops; to assist the local irrigation needs through construction of new cisterns and reservoirs and rehabilitation of existing Roman cisterns; to improve soil-water storage enhancement and soil erosion through the construction of dykes across the channels of valley areas—to thus mitigate drought. Other ongoing objectives are soil conservation through vegetation improvement, reseeding and tree belt planting; improvement of the post harvest of olives, and an integrated pest management adapted to desert conditions.

Images from our trips into the valleys of the region

Water Management and Rainwater Harvesting

In this area of limited water resources, there three possible sources of water: surface water, groundwater and water from other facilities. Although some groundwater can be found at depth, the quality of the water is brackish to highly saline and is not suitable for agriculture. Other water facilities is available to customers along the pipeline from Alexandria to Marsa Matrouh, but this is mainly available to the hotels along the coast, for tourism.

Surface water is the main source in this area, collected from runoff after heavy rains, through rainwater harvesting techniques.

This Wadi-Bed System is a flood-water management method, and consists of the building of stone dykes constructed across the wadis (which are ephemeral channels) to delay runoff water following a rainfall; this maximizes the infiltration of water into the wadi channels, also facilitating a considerable amount of water to be able to percolate to deeper soil layers.

These practices can also enhance soil quality and help to reduce soil erosion and degradation in this arid environment, and contribute towards biomass accumulation. However on average, only 2–3 flows pass through these wadi systems per year.

Images from the home of Sheikh Saied

Among the on-site trips we made was a day in the home of Sheikh Saied, local Bedouin leader and the head of his tribe.

As there is essentially no water in the area except for what falls as precipitation, even household water for most of the Bedouin homes is obtained by water harvesting—the collecting of precipitation runoff water— which is stored for family use in an underground cistern, an excavated below-ground water storage chamber. For many families, cisterns are the primary water source for domestic (drinking, washing, cooking, etc) and animal use.

During this visit, Dr. Soliman discussed with both Sheikh Said and his nephew the various issues regarding daily and long-term challenges the family faces, from water scarcity to the need for better methods to harvest olives and produce higher-quality olive oil.

Portrait of Sheikh Saied, 2017

NUWEIBA, South Sinai Peninsula

The Governorate of South Sinai is situated within the arid belt of North Africa, and is characterised by a Saharo-Mediterranean climate that is hyper-arid, with mean annual rainfall ranging between 10mm per year along the coast, and a maximum of 60mm per year in the higher areas. The landscape is dominated by rugged mountains, interspersed with steep-sided valleys (wadis). The geology of these mountains consists fundamentally of basement red granitic rocks with intrusions of volcanic rock. Along the bottom of the wadis run riverbeds that remain dry for most of the year, only temporarily becoming rivers during any intermittent floods. The typically sporadic rainfall of the region usually occurs between October and May, and often the entire yearly precipitation can fall within the space of a few days resulting in heavy flash floods. Despite the water conditions of the region, the Sinai Peninsula is home to a high level of biodiversity of plant and animal life and as a whole supports approximately 1285 plant species, including more than 50% of all the plants that are endemic to Egypt, 800 of which have been recorded in South Sinai. There are four main tribes of Bedouin people that inhabit the region.

The next leg of the research trip took us southward by plane via Sharm El-Sheikh, to the Bedouin town of Nuweiba, situated on the eastern coast of the Sinai Peninsula, 70 km south of Taba and 180 km north of Sharm El-Sheikh. Our goal was to research into the field of organic, desert agriculture through on-site visits with with the local Bedouin community. Our on-site visits were set up for us to better understand the hurdles farmers face when attempting to green or farm in the desert or in degraded environments. Some of these challenges regard soil fertility, and water conservation techniques that are needed to manage the very limited water resources of this arid area, and the added issue of saline groundwater. Here, we resided at an organic and permaculture-based farm, education center and resort at Habiba Bay, Nuweiba.

Map of Sinai Peninsula, indicating town of Nuweiba along the Red Sea coast | Click to enlarge

Habiba Bay

In Nuweiba we were hosted at Habiba Organic Farm, founded by Mr. Maged El Said in 2007, whose dream it was to create a community-based farm to benefit the people of South Sinai, bringing long-term solutions to food insecurity while also emphasizing environmental protection.

The ongoing mission of Habiba Organic Farm is to promote sustainable agriculture and the permaculture lifestyle within Nuweiba’s local community and the surrounding Sinai. The farm aspires to set a successful example to show what can be accomplished through sound organic farming practices in the desert, and serve as a paradigm to be followed by locals across the peninsula. Today, what was once a piece of empty, lifeless desert (in spite of its highly fertile soil), the area has become a production hub for wide variety of local grown organic products and agriculture has begun to flourish across the region.

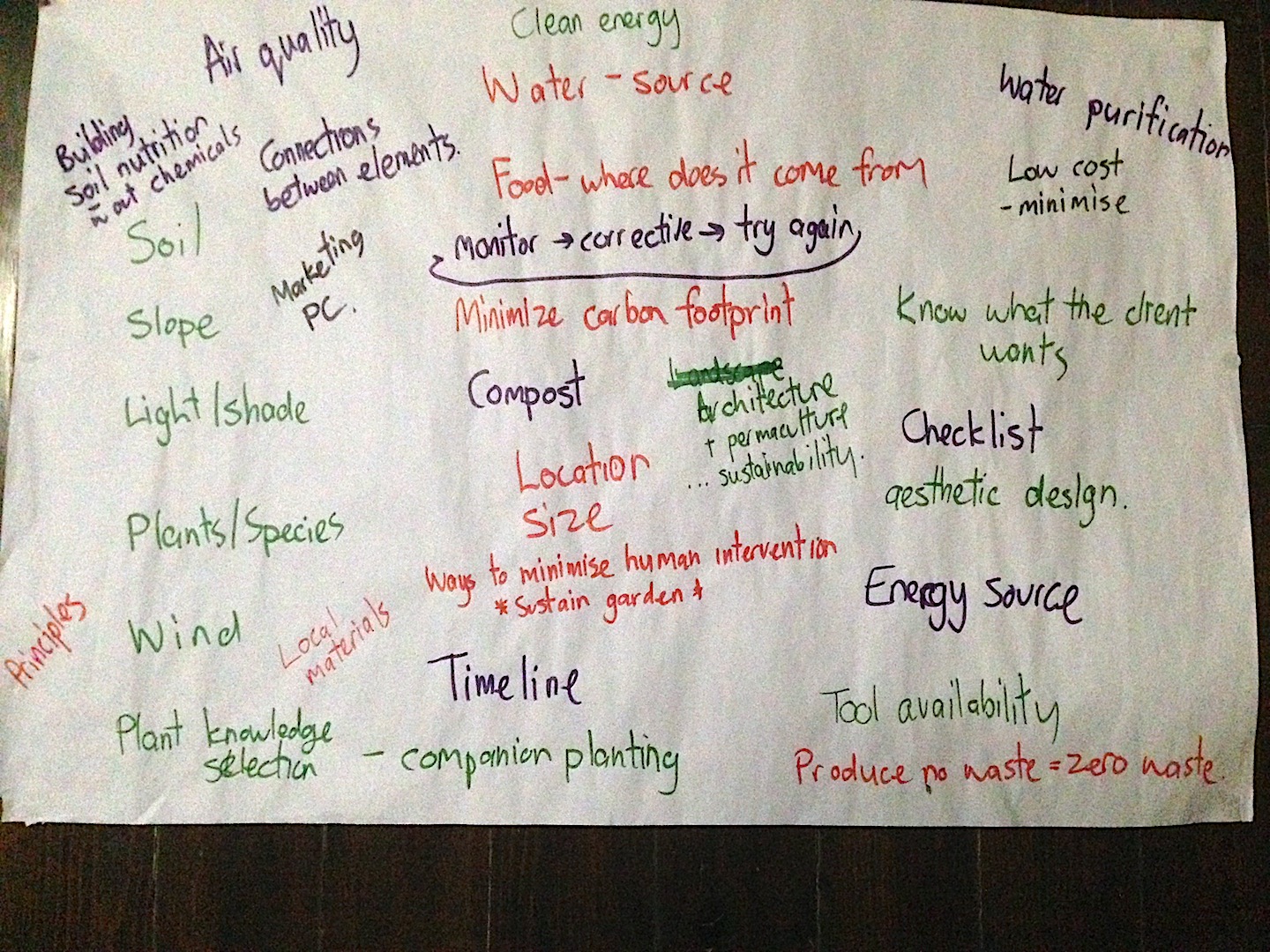

Moreover, the idea of Habiba is to be a field for experimental projects. Working in cooperation with the local branch of the Desert Research Center, has enables an environment for research and study for projects with flora and fauna in the desert. Habiba also hosts permaculture design certification (PDC) classes, to teach permaculture design principles, correct techniques for the region, the identification of plant pests and disease, compost production and the correct use of organic pesticides. Habiba also operates an after school learning center, and helps to coordinate WOMAD, a project to empower local Bedouin women and raise funds to enhance further education opportunities for their children.

Collaboration between Bedouin natives of the Sinai, with researchers from across Egypt and France, and the generous efforts of volunteers from around the world has led to the development of a high-yielding, purely organic farm that delivers healthy, fresh vegetables, fruits and herbs to the local community. Habiba trials new varieties of vegetables regularly, and acts as a hub for knowledge transfer between the farm, the Desert Research Center, several Egyptian universities, and three of the local Bedouin tribes.

Habiba Farm harvests many plant varieties all year round, including eggplant and asparagus.

Winter crops include Fava Beans, Swiss Chard, Kohlrabi, Kale, Beetroot, Salad Leaves, Rocket, Parsley, Dill, Fennel, Quinoa, Spinach, Onions and Garlic; a wide selection of tomatoes grown under cover.

Summer crops include Okra, Molokia, Peanuts, Melon, Water Melon, Pumpkin and Sesame Seeds. They also grow mulberries, olives, pomegranates, corn, medjoul dates, and a growing selection of herbs; including basil, wild mint (habak) and rosemary.

Newly added to the farm is the Moringa tree, a small ‘superfood’ native to the foothills of the Himalayas. For thousands of years, it has been cultivated by different cultures for its health benefits, from arid regions in India and Africa to dry regions in Central America and Mexico. It is a tree that can be grown in extremely arid regions with limited rainfall, and it tolerates a wide range of soils and can even be grown in lands bordering desertification.

Visits to other local farms

The Bedouin residents of the South Sinai harvest rainwater from the intermittent flash floods that occur during the winter months. Like in other arid regions, rainwater harvesting techniques allow them to cultivate a wide range of trees and crops throughout the year. The traditional Bedouin agricultural irrigated gardens—within the surrounding unmanaged habitat—is a fully organic food production system which dates from prehistoric times and is thought to be the world’s oldest and most resilient agro-ecosystem. These forest gardens or ‘food forests’ provide basic food needs to families, with some surplus going to the market; this is especially needed since the 2011 Egyptian Revolution which brought a massive crash to the local tourist industry, with food production as one of the few options left in a currently unstable and insecure economic circumstances of the South Sinai. Moreover, it has been shown through various studies that traditional bedouin practices and resource management techniques in these harsh conditions can not only conserve and also increase biodiversity in the environment, but also enhance food security by providing an economical strategy for increasing agricultural productivity..

View of the mountains of the South Sinai, farm of Sheikh Awad, El Legabe Wadi, 2017

Images from two small desert plantations with plant diversification that we visited in the area, demonstrating the capacity of local organic farming practices in the desert sand. On-site trip to the farm of Sheikh Awad (above), and Sheikh Mubarak (left), with Dr. Soliman and Dr. Ahmed.

Drip irrigation is used to manage the stored water resources in the walled forest gardens in which grow fruit trees and vegetables; low sand dams retain runoff during flash floods and built channels move water around in these gardens.

Breakdown of the crops produced in the region: Almond (94%), Grape, Fig, Apricot, Pomegranate, Apple, Olive, Jujube, Quince, Tomato, Peach, Walnut, Bean, Plum, Pear, Carob, Aubergine (20%).

Just as in the arid northernwestern coastal zone of Egypt, here too agriculture depends on careful management of the scarce natural water resources. As the region’s groundwater is saline, farmers in the S. Sinai also utilize surface runoff rainwater harvesting with different types of catchments. Water storage is a critical part of rainwater-harvesting practices, as rainfall is followed by long dry periods. The wadi landscape of the Sinai facilitates rainwater harvesting, as these valleys help funnel water into underground pools and dykes.

Bedouin Farm of Sheikh Mubarak, in Segar Wadi - South Sinai, 2017

View of Fjord Beach from the Nuweiba-Taba Road, one of the many other sites visited on the Sinai leg of this research trip.

Most heartfelt thanks go to each and every individual that made this trip both possible and such a fruitful experience.

Melina Nicolaides, Dir. of Activate

Banner image:

A large check-dam in Wadi Habis, Marsa Matrouh, on the north-western coast of Egypt, that extends all the way across the valley. This valley is one of 218 of this area, where multiple water-harvesting techniques are used by the local Bedouin farmers as flood water management to retard the runoff water coming down the ephemeral channel of the valley. Photo: M. El Baroudy, 2017

Images © Mohammed El Baroudy or Melina Nicolaides